Fish may turn yellow if frozen too fresh

What is the optimal point in time to freeze fish? At least not when it is too fresh, shows new research from Nofima.

Main findings of the project

- Haddock frozen pre-rigor developed yellow discolouration visible after 20 weeks in frozen storage.

- Both whole and filleted haddock developed discolouration.

- Cod did not turn yellow in the same way as haddock, but earlier research has shown it can, depending on the fish’s condition.

- Both pre-rigor frozen haddock and cod showed significantly higher liquid loss upon thawing, but this effect disappeared after a relatively short period in frozen storage for haddock. For cod, the effect remained pronounced even after one year of frozen storage.

Surprised? Entirely understandable. So were the researchers.

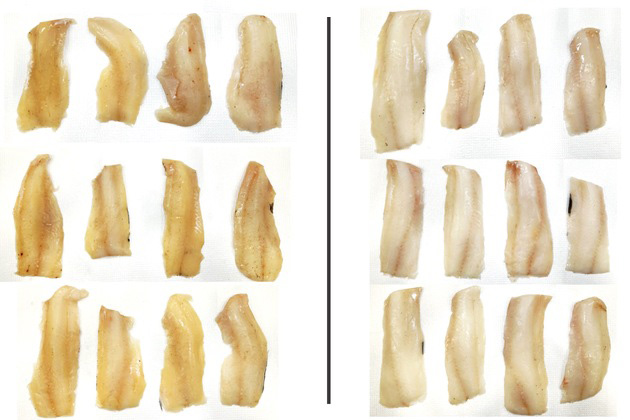

We are used to thinking “The fresher, the better” when it comes to food – and perhaps especially seafood. But look at the picture: haddock that was processed and frozen pre-rigor – that is, so fresh that rigor mortis had not yet set in – consistently turned yellow after just 20 weeks in frozen storage.

“Yellowing caused by ‘rigor energy’ has not been described in scientific literature. It is likely that the industry has not been fully aware of how significant this can be,” says Nofima researcher Svein Kristian Stormo.

By contrast, haddock frozen post-rigor showed no signs of discolouration.

Drip loss and quality

The project “Effect of rigor state before freezing of cod and haddock raw material” was carried out by researchers from Nofima, supported by the Båtsfjord trade fisheries group and Bluewild in Ålesund. Their aim was to document how the timing of freezing affects yield, quality and consumer appeal.

They studied the differences between fish frozen pre-rigor, in-rigor and post-rigor, and measured thawing loss, subsequent drip loss, and sensory qualities such as texture and colouration following chilled storage.

The differences in rigor status are described as pre-rigor, in-rigor and post-rigor – before, during, and after rigor mortis in the fish muscle. The researchers wanted to establish the effects of rigor status on thawing loss, subsequent drip loss, as well as sensory properties such as colour and texture subsequent to chilled storage after frozen storage.

The project is funded by FHF – The Norwegian Seafood Research Fund.

Project leader Svein Kristian Stormo, one of Norway’s foremost experts on freezing and thawing raw material, had expected that the level of liquid loss would prove the most interesting finding in the study.

“But I was wrong. What we in technical terms call thawing and drip loss of the raw material is indeed highly important to document. But the most surprising and interesting result was the discolouration,” says Stormo.

A financial risk for the industry

Both liquid loss and discolouration are highly unfavourable from a consumer perspective. The researcher also stresses that such deviations can lead to significant financial losses for the industry.

“The challenge is twofold. There is major focus on quality – on freezing the raw material as fresh as possible. But in this case, that very approach causes greater challenges with increased liquid loss and discolouration. It is important that the industry is aware of this problem and, in the long term, finds the best solutions to minimize such effects,” he says.

Historically, much of the fish frozen onboard vessels has been handled in ways that suggest relatively little of the fish has actually been pre-rigor at the time of freezing. However, there is much to indicate that opportunities to freeze pre-rigor raw material are increasing going forward.

“This is due to new routines with smaller hauls, better onboard handling, as well as an increase in the proportion of live deliveries to land-based facilities. In addition, cod farming will bring pre-rigor raw material handling further into focus,” says Stormo.

With greater emphasis on producing high-quality frozen raw material comes the need for fundamental knowledge of how rigor status affects raw material during freezing.

“In the first instance, it will be useful to conduct thorough documentation through controlled trials with both cod and haddock. These should monitor the effect that varying degrees of freshness have on raw material during freezing and frozen storage,” says Stormo.

Timing is key

When it comes to liquid loss – and therefore also loss of weight and profitability from the fish – the experiments clearly showed that there may be good reasons to wait until the fish has passed the first phase of rigor before being frozen. But it is equally important to carefully monitor the quality of the raw material.

“The results show that freezing pre-rigor raw material leads to significantly higher liquid release upon thawing. This applies to both haddock and cod, but in our experiment the effect with haddock disappeared after eight weeks of frozen storage. With cod, however, the increased liquid loss persisted throughout an entire year of frozen storage,” the researcher explains.

“Delaying freezing is one solution to avoiding this effect, but at the same time other degrading effects will take hold if the period is too long. For quality and practical reasons, it is essential to establish the optimal point in time for freezing,” he concludes.

What is rigor mortis?

Rigor mortis is the stiffening of the muscles following death. For fish such as cod, it may start within two hours but can also take a full day to set in.

- Fish before stiffness sets in is called pre-rigor.

- When stiffness is clearly noticeable, the fish is in-rigor.

- After one to three days, when stiffness subsides, the fish enters the post-rigor stage.