Worth to know about kveik

Brewing beer with kveik yeast has become very popular. Old traditions are being brought back and examined with a fresh perspective using modern methods of analysis.

What is kveik?

Kveik is the term for traditional Norwegian farmhouse yeast used in beer brewing.

Most common yeasts used in beer brewing belong to the genus Saccharomyces, and the most common species is S. cerevisiae. It has an elliptical cell shape with a large surface, making it well-suited for a life in nutrient-rich environments.Most yeasts grow on dead organic matter, and fruits and raw materials containing sugary plant juices are particularly susceptible. In Norway, common beer yeast can be found on the surface of apples and other fruits as well as in honey. Yeast can grow in both regular air and without any oxygen present. It is when we remove the air supply that the alcohol fermentation starts.

Kveik yeast typically grows by budding, where the bud eventually develops into a new yeast cell. The budding cycle makes it possible to see how many times a cell has divided through a deposit on the cell called a bud scar. A yeast cell can have up to 24 bud scars.

Until recently it was not possible to buy kveik yeast for beer brewing, as it had not been cultivated and stored in a yeast bank in line with other yeast types. Kveik yeast had simply sunk into oblivion, but thanks to enthusiastic and culturally aware beer brewers, kveik yeast is now about to be resurrected.

Lars Marius Garshol has written a book on the topic, and has been at the forefront of preserving the old kveik cultures. He is currently busy mapping kveik from different parts of the country, and Western Norway is particularly well represented as both the yeast and old beer brewing traditions have been honoured and preserved until the present day.

What distinguishes kveik from beer yeast

Kveik has not been used in sterile environments, and can therefore contain a mixture of several yeast species. It can also have elements of lactic acid bacteria. The most common type of kveik yeast is not unlike our ordinary bread yeast, but due to the Norwegian geography with tall mountains and deep fjords separating rural towns and farmsteads, the farmhouse yeast strains have grown and developed locally. Over time, the yeast’s genome has changed through natural mechanisms (mutations, rearrangements and/or crossing) and through selection due to chemical and physical conditions associated with local brewing methods.

Kveik yeast holds a special position among beer yeasts because it can be used for fermentation at higher temperatures, which allows beer to be fully brewed after only a few days. In addition, it can produce substances that allow the beer to develop distinctive flavours and aromas with local variations depending on the strain being used.

Long brewing history

There are long traditions for beer brewing. Old records on stone tablets suggest that beer was made from grain as early as 6,000 years ago in the areas around the Euphrates and Tigris, and 13,000-year-old residues of a beer have also been found in Israel.

Sadly, the records from Norway are more scarce, but we do have a point of reference in that the Gulating laws from around 1000 C.E. required every household to brew their own Yule beer. Local ingredients and local customs have resulted in many different varieties of beer. People used what they had available from grains, hops and herbs – often juniper, and local beer traditions were allowed to develop for generations.

Yeast from old brewing equipment

When beer was brewed in the old days, a yeast ring or yeast log was lowered into the beer foam during the brewing process or into the leftover yeast sludge after the beer had been drawn off. The yeast ring or yeast log had many cavities and pores where the yeast could attach. It would then be hung to dry and used again to add yeast to the next brewing batch.

Of course the yeast rings were far from sterile, and wild yeast – natural yeast from the surrounding environment and the air – could easily enter the beer and ruin it. Now that we are working on mapping the old yeast species, it is essential to obtain kveik from brewers at farms that are still brewing with this old yeast. It is also interesting to examine old yeast rings, yeast logs or brewing vessels that can still be found on some farms in Norway. You can then harvest the yeast by scraping dried yeast residues from the bottom of the beer barrels, or by using a piece from a yeast ring.

From brewing vessels to the lab – and back again

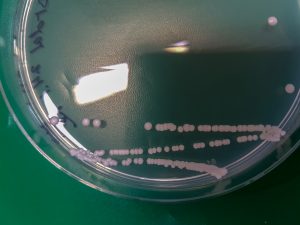

The food research institute Nofima has collaborated with Garshol to bring old kveik yeast back to life under laboratory conditions. The yeast will have excellent growing conditions in both fluids with nutrient-rich solid surfaces such as agar plates, where they form colonies. Eventually you will be able to distinguish various strains from each other and use laboratory techniques to identify and map their properties. Many strains are now frozen so that they are preserved for the future.

At Nofima’s laboratory we’ve examined kveik from local farms from different locations across Western Norway. Pure cultures have now been tested for a variety of growth properties such as their ideal temperatures (4–45℃), acidity and a broad range of nutritional elements. They have also been identified by sequencing a small specific region of the genome (using a so-called Internal Transcribed Spacer or ITS) which can separate the strains down to the genealogy and species level.

There are still many things we don’t know about kveik. Some of these yeast strains are now shared globally and are being examined for several growth properties and different genome analyses (DNA analyses – PCR fingerprint data). The results suggest that all kveik yeast belongs to the same yeast family but with local genetic variants. With its unique properties in terms of robustness and taste, kveik has great potential in industrial beer brewing.

Taste for the future

We have carried out laboratory-scale mini-fermentation to document the properties of individual strains. Although most originate from the species Saccharomyces cerevisiae, it turns out that they have a fermentation ability that is completely unique. Kveik has a high temperature tolerance, can ferment a beer to completion in just a few days, and provides a whole new range of flavors.

A big question is which of these yeast cultures provide the grounds for tasty and characteristic beer products fit for industrial production, and whether they should be used alone or in combination. The taste of kveik beer varies with the yeast strains used, and it is the local varieties that are of interest here.

Contact person

Research areas

Product development

Topics

Drink