Carbone dioxide a cause of kidney stones in rainbow trout

Scientists at Nofima have investigated the impact of carbon dioxide in water on the development of kidney stones in farmed rainbow trout. The research shows a clear correlation.

In short, the results indicate that the higher the concentration of carbon dioxide (CO₂) in the water during the juvenile stage, the greater the proportion of fish that develop kidney stones (also known as nephrocalcinosis). There is also a clear correlation between the concentration of carbon dioxide and the severity of the condition.

Why is there carbon dioxide in the water?

During the juvenile stage, rainbow trout (and salmon) are farmed in tanks with freshwater on land. If fish density is high and water exchange is low, the level of carbon dioxide increases. As the fish breathe, they take oxygen through their gills and release carbon dioxide. In practice, there is therefore always some carbon dioxide in the water in a tank with farmed fish.

It is important to keep the concentration low enough so as not to harm the fish, and Nofima has research that provides answers.

About kidney stones

Nephrocalcinosis is a rapidly growing kidney disease in farmed salmonids. The main function of the kidneys is to purify the blood and secrete urine. They are also among the fish’s largest blood-forming and immunological organs. When smolts are transferred to sea with defective kidneys, they cope poorly with the challenges in the marine environment, even though the carbon dioxide concentration there is very low.

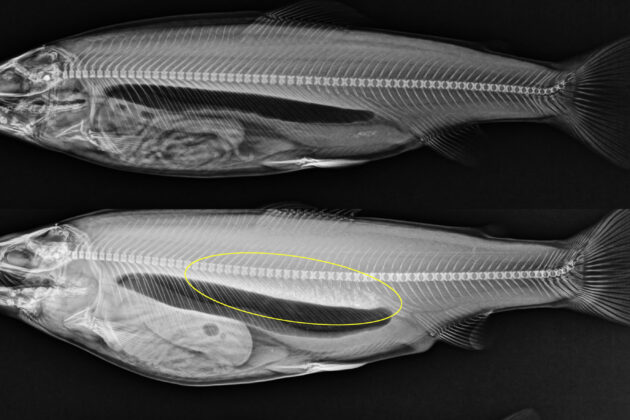

“It is uncertain how painful nephrocalcinosis is, and when it becomes truly serious. The fish may look perfectly healthy on the outside, but have destroyed kidneys,” says veterinarian Kirsti Hjelde at Nofima. She has contributed to the further development of X-ray diagnostics that make it possible to detect kidney stones in live fish.

It has long been assumed that carbon dioxide affects the development of nephrocalcinosis, and a general recommendation to fish farmers has been to keep carbon dioxide below 15 mg/l of water in juvenile facilities. However, this recommendation has not been well documented. Now, Nofima’s research shows that 13 mg CO₂/l of water caused development of nephrocalcinosis in 5 percent of the fish. When the fish were farmed in water containing 26 mg CO₂/l, more than 40 percent developed nephrocalcinosis.

“Our results show that CO₂ values of 13 mg/l and above increase the risk of nephrocalcinosis in rainbow trout,” says Ingrid Lein at Nofima.

“The extent and severity of kidney stones increase steadily as CO₂ concentration rises.” Lein is careful to point out that she does not believe carbon dioxide is the only cause of nephrocalcinosis in rainbow trout, but that it is clearly a very important causal factor.

“For salmon, we know the situation is more complex, but there is every reason to believe that carbon dioxide is also an important part of the causal picture for salmon,” she says.

The method is the key to more knowledge

Behind the concrete results from the research lies method development that began as part of CtrlAQUA (a Centre for Research-based Innovation (SFI)) a few years ago. Nofima has now further developed the method through experiments at the research station in Sunndalsøra, Norway.

“We now have a model system where we can induce nephrocalcinosis in rainbow trout and measure the effect on the fish. With this setup, it becomes easier to investigate other risk factors, interactions and measures against kidney stones in farmed fish,” says André Meriac at Nofima.

He hopes the aquaculture industry will dig deeper into the causes of nephrocalcinosis and is ready to help clarify causes and contribute to healthier farmed salmon in commercial facilities.

X-rays measure the effect

To measure the effect of various treatments, Nofima uses X-rays on live fish on a large scale. With X-rays on live fish, scientists can detect the kidney stones, which are crystals in the kidneys. Previously, diagnostics were limited to taking tissue samples and the need to kill the fish to study the kidneys.

“With X-rays, we avoid harming the fish. In this experiment, we took live X-rays of all individuals before they were transferred to sea and will take new X-rays at the end of the experiment to understand how the different treatments during the juvenile stage have affected how the fish coped in the sea,” says Hjelde.

The research is funded by the Norwegian Seafood Research Fund and is a collaboration between Nofima and several industry partners in aquaculture.

About the research

The project, called “Early Development in Rainbow Trout”, is funded by FHF and aims to find answers to several health challenges in rainbow trout. The project leader is Grete Bæverfjord at Nofima.

The goal of the project is to develop new knowledge about production conditions that will contribute to the normal development and function of the heart, kidneys, and gills in rainbow trout, as well as provide recommendations on “best practice” for farming small trout.

The project started in 2023 and will conclude in autumn 2026.

Facts about the experiment concerning kidney stones:

- The fish commenced first-feeding in freshwater (at 12°C) at Nofima in Sunndalsøra in April 2024. When the fish reached 15 grams, they were divided into five groups that received different additions of CO₂: 0, 10, 15, 20 and 25 mg CO₂/litre. The actual concentration of CO₂ in the tanks was 7, 13, 17, 22 and 26 mg CO₂/litre.

- After 3 months, the fish, which were then about 100 grams, were transported to the Institute of Marine Research in Austevoll at the west coast of Norway, where they are kept in experimental sea cages until they reach a size of about 4 kg.

- The fish were diagnosed with X-rays at the start of the experiment, at the end of the freshwater phase, and after 4 months at sea. They will also be diagnosed at the end of the experiment in October 2025.

Contact persons

Research areas

Farmed fish

Topics

Fish health

Research facilities

Research Station for Aquaculture – Sunndalsøra

Files and Links